Can you really learn about investing by studying the work of the Beatles? Absolutely. The level of success the Beatles achieved in songwriting and recording is so extraordinary — sales of over 1 billion units of music worldwide — that key attributes of their techniques are certainly worthy of study, even from the seemingly unlikely perspective of an investor.

Table of Contents:

- Introduction

- Master the Art and Mathematics of Timing

- Overcome Your Biases and Be Willing to Do the Work

- Know Where the Value Lies — In a Portfolio or In a Batch of Songs

- Force Yourself to Sit Quietly, Read Widely, Listen Intently

- Follow Your Successes With a Redoubling of Effort

- Kings of Long-Term Compounding: The Beatles Versus Warren Buffett

The challenge that stands before a professional investor each year is the same challenge that faces a recording artist. They each want to top last year’s performance, and they each need 10 or 12 new pieces of material to achieve the goal. The “material” a recording artist needs is 10 or 12 new well-written songs, while an investor needs 10 or 12 new well-researched stocks. In each case, the work must be of high quality, so as to produce at least two or three big “hits” to drive the album’s or the portfolio’s performance. Think of your all-time favorite music album, and then imagine it without the top 3 songs — it’s no longer your favorite album. It’s the same with investing: Lop off your top 3 performers each year, and you won’t generate outsized returns.

5 Investment Lessons from the Beatles

- Master the Art and Mathematics of Timing

- Overcome Your Biases and Be Willing to Do the Work

- Know Where the Value Lies — In a Portfolio or In a Batch of Songs

- Force Yourself to Sit Quietly, Read Widely, Listen Intently

- Follow Your Successes With a Redoubling of Effort

Master the Art and Mathematics of Timing

High achievement in either music or investing hinges on a mastery of the mathematics and art of timing. Timing is essential to a well-played song; timing is often the determinant of success in capital allocation.

It’s not often discussed, but a key mathematical trait of a pop song is the ratio of beats per minute (or “bpm”) at which a tune is performed. (You may remember a music teacher using a metronome to set a tempo.) For a songwriter, determining the optimal beats per minute tempo for a song is a key decision. For example, the pensive Beatles song “Yesterday” was recorded at 97 beats per minute, giving the song dramatic weight and heightening the attention given to the melody and lyrics. Meanwhile, the high-energy song “I Want to Hold Your Hand” was performed at 131 beats per minute, a breakneck tempo that energized shrieking crowds and made the song the first #1 U.S. hit for the Beatles in 1964. If you swapped the tempos of “Yesterday” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” you’d drain emotion from the former and drain energy from the latter. The decision must fit the situation.

It’s the same with investing. You use judgment to optimize the timing of deployment of capital depending on the situation. Consider the “tempo” at which we entered our position in the retailer PetSmart (PETM) in 2010. As value investors, we are price-sensitive and often methodical in our purchases, but we built the PetSmart position at an uncharacteristically rapid cadence following a March 2010 PetSmart earnings report that revealed better sales measures and cash flow than was implied by the stock’s low valuation. We purposefully bought the stock as it rose over a period of days, as our quantitative and qualitative work confirmed the firm was seriously undervalued. After our initial PetSmart buy, we bought some shares 10% higher, then bought more 2% higher than that, and eventually bought more shares 7% above that. It was a situational decision to deploy capital into the investment quickly before all the good news got into the stock. It was atypical for us, but in this case it made sense; the stock more than doubled in price during the following quarters.

On the other hand, at the time of this writing we’re building a position in another retail stock but doing so at a “Yesterday” pace rather than at the stepped-up “I Want to Hold Your Hand” tempo we used for PetSmart. The situation is different. This company is in an unfolding, turnaround position, and a new management team is still working out a revamped operating plan. We’re being careful to pay prices only at the bottom end of our assessment of the company’s value range, and this slower tempo is getting us better prices. It’s a situational call.

In music and business, history shows timing matters when it comes to wealth creation. Consider the unfortunate case of Pete Best, sometimes referred to as “the unluckiest man in rock music history.” He was the Beatles’ drummer for two years but was replaced by Ringo Starr just as the Beatles were signed to a record contract. It was apparently determined that Best didn’t quite have the timing skills to serve as their rhythm backbone. The difference in net worth between Ringo Starr and Pete Best today? Probably $200 million.

Overcome Your Biases and Be Willing to Do the Work

The Beatles team member an investor might learn the most from is their producer, George Martin, often referred to as “the fifth Beatle.” Martin had an ear for music and a nose for value. Whereas all the other record labels in London had rejected the Beatles by 1962, Martin signed them to their first contract, which was certainly a “value investment” for his record label — it promised the Beatles just one penny per double-sided record sold. (That is, the four Beatles and their manager were to share the one penny royalty. Don’t worry, they later got a raise.)

Like a practical portfolio manager, Martin looked past his own biases — his first love was classical music — and realized that audiences would find great value in the energy, talent and freshness of the Beatles. Martin didn’t stop at signing the group. He then began the down-in-the-trenches work of developing the Beatles in the studio. He was skilled at taking the “raw material” bits of musical genius that Lennon and McCartney provided, and he repeatedly fashioned the bits into great songs. In his memoir All You Need is Ears, Martin writes:

“[The Beatles] had a large amount of raw material which simply needed shaping. A lot of the songs we made into hits started life as not very good embryos. When they had first played me ‘Please Please Me’, it had been in a very different form…. I might say, for instance: ‘Please Please Me’ only lasts a minute and ten seconds, so you’ll have to do two choruses, and in the second chorus we’ll have to do such-and-such.”

Martin is thinking like a portfolio manager. Come to think of it, when it came to music, Martin was the Beatles’ portfolio manager. He knew where there was potential value in the raw material, and he was willing to work hard to make the most of it. His work ethic would benefit any portfolio manager. Says Martin, “It is stamina, the ability to do a professional job year in, year out, that is hard to achieve. You can’t rest on your laurels. You can’t let up for a moment in seeking the best result of which you are capable.”

As investors, we work to maintain standards worthy of George Martin, staying rational and overcoming our biases to find value in the market wherever it resides — not just in places where we’ve found it before. And upon identifying the “raw material” that is of value, we set about to squeeze the most return possible from the situation by doing hours of solid valuation work, cash-flow analysis, and price-sensitive trading.

Know Where the Value Lies — In a Portfolio or In a Batch of Songs

Some people think all an investor does is make a list of good companies and then buy the cheap ones. But buying and collecting companies is not how money’s made in investing. The careful investor must think two steps ahead — to what conditions will allow him to sell the investment at a much higher price, as well as a range for what that higher price will be. On a daily basis, the sharp portfolio manager makes note of where the greatest value (the upside) lies within his own portfolio at that time, thereby making himself ready to make optimal portfolio moves should market prices lurch significantly up or down.

There’s no better example of “knowing where the value lies” in a portfolio (of songs) than in looking at the business strategy, if you will, of Paul McCartney’s song selection at his live concerts over time. In the years just after the break-up of the Beatles in 1970, McCartney began issuing solo albums of new songs and at his live concerts he initially refused to play any Beatles songs at all. In hindsight, this was an exceedingly rational portfolio-management move on McCartney’s part, as his new solo songs had the most “upside.” By not playing Beatles songs, McCartney kept himself from becoming merely an oldies act and instead built a burgeoning audience of listeners who were forced to focus on his new investments in songwriting. The result was the successful development of a McCartney solo career.

Now fast-forward to May 2012 to a concert McCartney played in Mexico City before an audience of 250,000 fans at the end of a Latin American tour. At this show, fully 65% of the songs he chose to play were Beatles songs. With his place in music history secure, McCartney was wise to reach into his portfolio and give the market (250,000 fans) what they wanted. Do we know whether McCartney is tired of singing “Hey Jude” or “All My Loving” after all these decades? We don’t know, but McCartney seemed more focused on delivering value to those who had invested the effort to attend his show. Rather than following his own biases, he was thinking about the eyes of other beholders to determine which of his holdings would “sell” the best at what might be his last-ever show in Mexico. McCartney clearly knows where the value lies within his portfolio as of 2012 — and something tells me that at 70 years old, he might still enjoy the sound of a quarter-million fans singing along to a song he wrote.

Stay up to date

Subscribe to receive our quarterly investor letters and market updates.

Force Yourself to Sit Quietly, Read Widely, Listen Intently

Mathematician Blaise Pascal once famously noted, “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” If that quote is true, it’s bad news for today’s professional investors. Why? Because if not careful, the professional investor of today has a strong likelihood of drowning in distractions and meaningless electronic-news updates that don’t provide insight into the intrinsic value of investments. A person who doesn’t keep his mind open and develop a strategy for taming this jungle of information will never create the mental space to come up with the big-picture ideas that can create big value in an investment portfolio.

Could it be that the musical excellence achieved over time by the Beatles was fueled by the involuntary isolation and stifling lifestyles they were forced to lead once they could no longer go out in public due to the crushing fame of Beatlemania? John Lennon once described life on tour with the Beatles amidst their thousands of admirers as “one more stage, one more limo, one more run for your life.” Since the Beatles couldn’t easily leave their homes or hotels, they perhaps had surprising amounts of time for reading, television and, presumably, generating song ideas.

John Lennon’s mind was always open to ideas, and he was a voracious reader and clever lyricist. He had a gift for translating complex ideas from the newspaper, books and philosophical readings into sweeping, anthem-like song lyrics such as “All You Need is Love,” “Revolution,” and “Give Peace a Chance.” He simplified in a poetic fashion the big-picture concepts that were already on the minds of listeners.

Lennon’s creative process often included reading the newspaper or other written materials and then plucking song characters and story lines from the pages, something he did on the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album. You could argue that a professional investor does the same thing: Each week and each month he or she is converting the sum total of his readings and knowledge into precise expressions via the purchase and sale of securities.

McCartney, too, was open to influences well beyond traditional rock-and-roll, and he was a good and curious listener. For instance, while witnessing a concert performance of a Bach Brandenburg Concerto in 1967, McCartney had an “aha” moment upon hearing the sound of an instrument he’d never heard before — the piccolo trumpet. This was during the time when the Beatles were recording “Penny Lane,” and he went to George Martin and inquired about the rarely used orchestral instrument, saying, “Why can’t we use it?” Martin quickly hired a player, McCartney wrote some music and the rest is history. The piccolo trumpet gives “Penny Lane” a distinctive, instantly recognizable sound and was a bold and unusual move for a rock band at the time.

At our firm, we believe one of our most long-lasting investment advantages is our commitment to taking time each week to “sit quietly in a room” in our quest to identify value. The benefits of applying sustained focus accrue over time and are too great to ignore in an era characterized by short-termism and distraction. We’ll be drawing on this learning from the Beatles for decades to come.

Follow Your Successes With a Redoubling of Effort

Anyone who achieves success at a high level over long periods of time should probably ask himself: how should I respond to success if my goal is to continue having success?

You could do a lot worse than to copy what Paul McCartney did after the Beatles began to have success. After the Beatles hit the big time in England in 1963 with hit songs like “Please Please Me,” McCartney did a curious thing: He began taking piano lessons. It was an interesting move, as McCartney had already proven himself a versatile musician. He’d spent five years in the Beatles and its predecessor bands, had already switched instruments once effortlessly (from guitar to bass), and he was growing as a songwriter and singer within the band, egged on by a friendly competition with John Lennon. But his ambition and curiosity led him to want to further develop his musicianship.

McCartney was not a complete stranger to the piano; there had been a piano in the house in which he grew up in Liverpool. But studying piano with a classical instructor from the Guildhall School of Music in London was a step up. Who knows how many world-famous compositions benefited from McCartney’s decision to better himself on the piano — particularly when you think of how many later Beatles songs were clearly composed on piano: “Penny Lane,” “Let it Be” and “Hey Jude,” for example.

In sum, the achievement of investment excellence over long periods is by definition a long and winding road, and it pays to study examples of long-lasting success such as that achieved by the Beatles. It’s been 50 years since the Beatles first stepped into the studio with producer George Martin in September 1962, and so far the band’s portfolio is aging well. In redoubling our commitment to excellence and arming ourselves with insights from our interdisciplinary study of the Beatles, we too hope to build a lasting legacy in our field.

Kings of Long-Term Compounding: The Beatles Versus Warren Buffett

The remarkable thing about both the Beatles and Warren Buffett is that they both came of age in the early 1960s, they performed in their fields at a high level for many years, and they both remain icons of excellence within their respective genres after half a century.

As investors, when we think of success, we can’t help but think of compound annual growth rates. We can view Buffett’s record of compounding in numbers provided annually by his company, Berkshire Hathaway. But for the Beatles, we must create a measure of compounding. Allow us, then, to illustrate the compounding power of the influence and fame of the Beatles using a comparison of attendance at 1960 (pre-fame) Beatles club dates with a very recent Beatles data point — the number of attendees at a 2012 Paul McCartney concert. (With John Lennon’s death in 1980 and George Harrison’s passing in 2001, Paul McCartney must stand in as a current-day incomplete proxy for the Beatles.) In May 2012, during the time this letter was written, McCartney concluded a South American tour with an outdoor concert in Mexico City at which he played nearly three hours of music before 250,000 attendees. Of the 40 songs McCartney played, 26 were Beatles songs, including “Drive My Car,” “Eleanor Rigby,” “Let it Be,” “Helter Skelter” and “Hey Jude.”

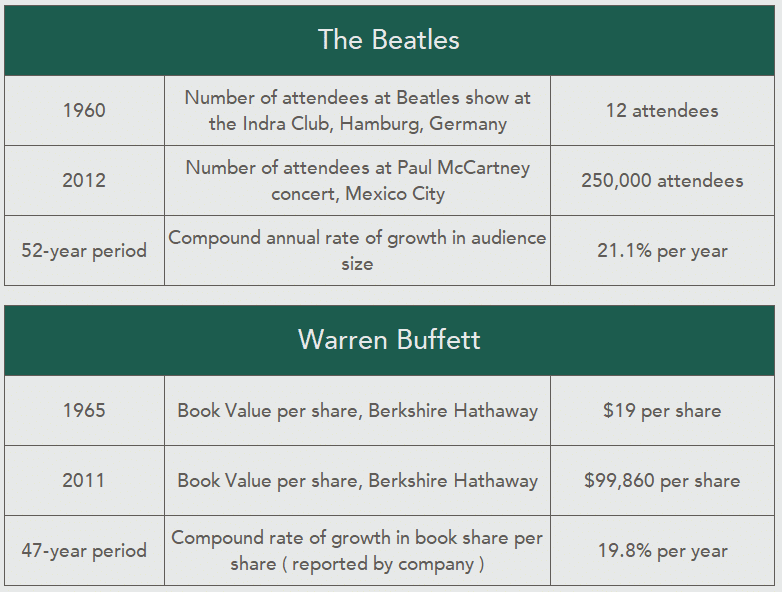

Even the Beatles had to start somewhere, and the Beatles famously cut their teeth in Hamburg, Germany, in 1960, serving as the house band at dank, seedy clubs such as the Indra Club in the city’s red-light district. As the accompanying tables illustrate, the 52-year rate of growth in Beatles attendance is over 21% per year — a similar rate of growth to the 19.8% rate at which Warren Buffett has compounded the book value of Berkshire Hathaway over the last 47 years. (Plus, even though Buffett has been known to strum the ukulele and sing a tune at times, he hasn’t produced any #1 hit singles, while the Beatles produced 27 of them.)

Tables are for illustrative purposes only.

And though success in music and the arts really shouldn’t be measured in dollars, it’s hard not to mention that the estimated net worth of Beatle Paul McCartney alone is estimated to be in the $800 million range. Add in the wealth of John Lennon’s widow (Yoko Ono) along with that of drummer Ringo Starr and the estate of the late Beatle guitarist George Harrison, and the estimated total tops $1.5 billion — and the Beatles machine still generates cash.

Paul Moomaw, CFA

Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed reliable but is not necessarily complete. Accuracy is not guaranteed. Any views expressed are subject to change at any time, and Nixon Capital disclaims any responsibility to update such views. References to specific securities are not intended and should not be relied upon as the basis for anyone to buy, sell or hold any security Portfolio holdings and sector allocations may not be representative of the portfolio manager’s current or future investment and are subject to change at any time. This information is not to be reproduced or redistributed to any other person without the prior consent of Nixon Capital LLC.